This Saturday, 28th September, marks forty years since the closure of the last two mines in the Somerset Coalfield, Lower Writhlington and Kilmersdon. Both pits stopped production in 1973 after Portishead Power Station was converted from coal to oil and saw an end to the mining industry in the Somer Valley.

Nowadays, visits to Kilmersdon and Writhlington wouldn't be able to tell you much about life working in the mines, but the whole area is rich with mining history. There is evidence to suggest that the colliery in Kilmersdon was being used as far back as Roman times, making it one of the oldest in the area. Several sources agree that there is evidence showing that coal was being dug in the Mendips in 1305 and that the colliery area was in use in 1437. The fortieth anniversary of the closure this coming weekend is being remembered by former colliery workers and their families throughout the district, although the years have taken a toll on their numbers.

As well as being the last of the Somerset Collieries, Kilmersdon can also boast being the last mine to use a gravity-operated incline and Writhlington, the last to use a steam winder before it inherited an electric one from the closing of Norton Hill in 1966. The wheel outside Radstock Museum came from Kilmersdon Colliery, which was known locally as Haydon Pit, and continues to serve as a reminder of the history of the town.

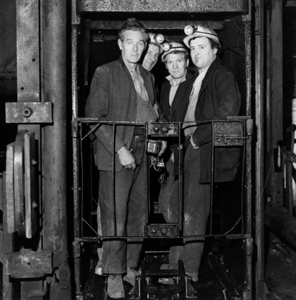

"The industry defined the gritty character of this area, its economy and its very appearance," said Radstock Museum Volunteer, Wendy Walker. "The museum is surrounded by hills created by old slagheaps, now wooded over and memories are still sharp. Every year the Somerset miners hold a reunion at the museum and every year they enjoy exchanging stories of their years in the pits."

The Writhlington Coal Company, which ran the majority of the mines in the Radstock area, acquired Kilmersdon in 1928. In 1967, the Kilmersdon/Writhlington mines produced its highest tonnage of saleable coal, 280,000, that's 1,135 tons per working day with a workforce of only 670 men, making them two of the most financially viable pits in the Somerset Coalfield.

The run-up to the closures, which put more than 400 men out of work, was long and bitter. At the start of 1972, clouds were gathering rapidly over the whole national scene, with a national strike for better wages for Britain's miners. By February that year, there were power cuts, a national state of emergency and a three-day working week, plus a warning by the National Coal Board that uneconomic pits might be closed by a lengthy dispute.

That May, Portishead Power Station stopped taking Somerset coal and in November, it was announced that up to seventy Somerset miners would be made redundant. The final announcement of the closures was made in May 1973.

The last word in the local media was given to Vic Sage, who had worked in the coalfield for 46 years. At the age of fourteen, he had been harnessed to the trucks of coal by the notorious 'guss and crook' rope and chain harness. Now his years of toil underground were over. "It's been hard graft and I'm not sorry to see it go," he told the Somerset Guardian. However, like many of his colleagues, he mourned the loss of comradeship.

Tony Evans, Overman at Kilmersdon Colliery and speaking to The Journal this week, agreed: "The average age of the miners at Kilmersdon was about 55, they were mostly glad to move on to other things.

"We had to work as a team and we all helped one another in times of need."

Unlike other mines in the area, such as Wellsway and Norton Hill, Lower Writhlington and Kilmersdon recorded the lowest accident rate in the South West and Wales area. Wellsway pit suffered one of the most devastating disasters, when, in 1839, twelve miners were killed when a rope lowering them into the pit snapped. An explosion killed ten workers at Norton Hill in 1908. Memorials for the lives lost can be found in St John's Churchyard and Westfield Drive, near the Sun Chemical site, in Westfield.

Kilmersdon and Lower Writhlington can also boast the lowest absentee rates in the whole British mining industry and was well known for being dispute-free with outstanding men/management relationships – despite the Somerset Coalfield being difficult to work because of the geology of the area. It is also for this reason that the Writhlington spoil heap or 'batch' is a Site of Special Scientific Interest because of the rich collection of fossils found in the spoil.

The past forty years has seen both areas change considerably, with barely any resemblance left of the mines that used to dominate the landscape.

Radstock Museum has recently been awarded £10,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund for 'Mining the Past,' a project which will enable local schoolchildren to record the memories of surviving miners.

"Through this project and through the permanent record of the Somerset Coalfield contained in the museum, we are paying tribute to the miners who gave this district its industrial heritage and special character," Wendy Walker concluded.